A new, streamlined version of Intervention Central is coming in December 2023. The new site will eliminate user login accounts. If you have a login account, be sure to download and save any documents of importance from that account, as they will be erased when the website is revised.

Main menu

How To: Structure Classroom Data Collection for Individual Students

![]() When a student is struggling in the classroom, the teacher will often implement an intervention matched to the student's deficient academic skills. However, classroom interventions are incomplete if the teacher is not also collecting data to document whether those interventions are actually benefiting students. Indeed, an intervention can be viewed as ‘fatally flawed’ (Witt, VanDerHeyden & Gilbertson, 2004) if it lacks any one of these 4 data elements:

When a student is struggling in the classroom, the teacher will often implement an intervention matched to the student's deficient academic skills. However, classroom interventions are incomplete if the teacher is not also collecting data to document whether those interventions are actually benefiting students. Indeed, an intervention can be viewed as ‘fatally flawed’ (Witt, VanDerHeyden & Gilbertson, 2004) if it lacks any one of these 4 data elements:

- Problem definition. The teacher clearly and specifically defines the presenting student problem(s) needing intervention. If the student problem is not clearly defined, the teacher cannot accurately measure or fix it.

- Baseline performance. The teacher assesses the student’s current skill or performance level (baseline performance) in the identified area(s) of concern. If the teacher lacks baseline information, he or she cannot judge at the end of the intervention how much progress was actually made.

- Intervention goal. Before starting the intervention, the teacher sets a specific outcome goal for student improvement. Without a goal in place before the start of the intervention, the teacher cannot judge at the end of the intervention whether it has in fact been a success.

- Ongoing progress-monitoring. The teacher selects a method to monitor the student’s progress formatively during the intervention. Without ongoing monitoring of progress, the teacher is 'flying blind', unable to judge to judge whether the intervention is effective in helping the student to attain the outcome goal.

Bringing Structure to Classroom Data-Collection. The Student Intervention: Monitoring Worksheet. As teachers take on the role of ‘first responder’ interventionist, they are likely to need guidance – at least initially—in the multi-step process of setting up and implementing classroom data collection, as well as interpreting the resulting data.

as well as interpreting the resulting data.

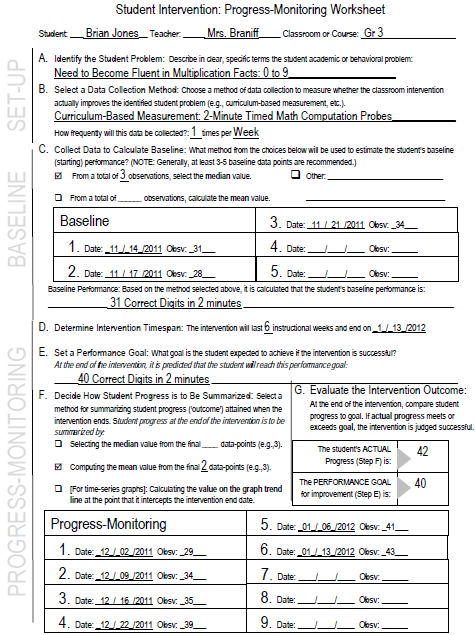

A form designed to walk teachers through the data-collection process-- The Student Intervention: Progress-Monitoring Worksheet—can be downloaded HERE. (A completed example of the Worksheet also appears in the figure to the right.)

The Worksheet is a 7-step ‘wizard’ form to show teachers how to structure their progress-monitoring to ensure that their data collection is adequate to the task of measuring the impact of their classroom interventions:

- Identify the student problem. The teacher defines the student problem in clear, specific terms that allow the instructor to select an appropriate source of classroom assessment to measure and monitor the problem.

- Decide on a data collection method. The teacher chooses a method for collecting data that can be managed in the classroom setting and that will provide useful information about the student problem. Examples of data collection methods are curriculum-based measurement (e.g., oral reading fluency; correct writing sequences), behavior-frequency counts, and daily behavior report cards. When selecting a data collection method, the teacher also decides how frequently that data will be collected during intervention progress-monitoring. In some cases, the method of data collection being used will dictate monitoring frequency. For example, if homework completion and accuracy is being tracked, the frequency of data collection will be equal to the frequency of homework assignments. In other cases, the level of severity of the student problem will dictate monitoring frequency. In schools implementing Response to Intervention (RTI), students on Tier 2 (standard-protocol) interventions should be monitored 1-2 times per month, for example, while students on Tier 3 (intensive problem-solving protocol) interventions should be monitored at least weekly (Burns & Gibbons, 2008).

- Collect data to calculate baseline. The teacher should collect 3-5 data-points prior to starting the intervention to calculate the student’s baseline, or starting point, in the skill or behavior that is being targeted for intervention. The student’s baseline performance serves as an initial marker against which to compare his or her outcome performance at the end of the intervention. (Also,--because baseline data points are collected prior to the start of the intervention--they collectively can serve as an prediction of the trend, or rate of improvement, if the student’s current academic program were to remain unchanged with no additional interventions attempted.). In calculating baseline, the teacher has the option of selecting the median, or middle, data-point, or calculating the mean baseline performance.

- Determine the timespan of the intervention. The length of time reserved for the intervention should be sufficient to allow enough data to be collected to clearly demonstrate whether that intervention was successful. For example, it is recommended that a high-stakes intervention last at least 8 instructional weeks (e.g., Burns & Gibbons, 2008).

- Set an intervention goal. The teacher calculates a goal for the student that, if attained by the end of the intervention period, will indicate that the intervention was successful.

- Decide how student progress is to be summarized. A decision that the teacher must make prior to the end of the intervention period is how he or she will summarize the actual progress-monitoring data. Because of the variability present in most data, the instructor will probably not elect simply to use the single, final data point as the best estimate of student progress. Better choices are to select several (e.g. 3) of the final data points and either select the median value or calculate a mean value. For charted data with trendline, the teacher may calculate the student’s final performance level as the value of the trendline at the point at which it intercepts the intervention end-date.

- Evaluate the intervention outcome. At the conclusion of the intervention, the teacher directly compares the actual student progress (summarized in the previous step) with the goal originally set. If actual student progress meets or exceeds the goal, the intervention is judged

Attachments

References

- Burns, M. K., & Gibbons, K. A. (2008). Implementing response-to-intervention in elementary and secondary schools. Routledge: New York.

- Witt, J. C., VanDerHeyden, A. M., & Gilbertson, D. (2004). Troubleshooting behavioral interventions. A systematic process for finding and eliminating problems. School Psychology Review, 33, 363-383.